Garnett Genuis writes: Girard GNJ - Tracked changes

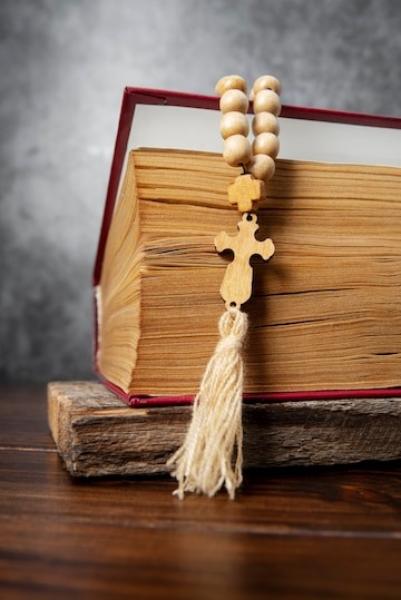

René Girard was a Christian anthropologist, whose insights about the ways communities operate shed light on the persecution of minorities. Why do majority communities in certain parts of the world choose to spend time and resources harassing minority communities that do not threaten them? There are a variety of different explanations, but I think Girard has one of the best. Some would argue that minority persecution is the result of religious or political beliefs. When new interpretations emerge, which dehumanize minority groups, they establish the conditions where violence can occur. But this does not explain why these new interpretations emerge or come to dominate. Other explanations for minority persecution emphasize competition over resources. But violence is often very costly in terms of resources spent. Also, this explanation does not help us to understand why certain minorities in particular are targeted. Girard argues that there is something about the human condition that often leads to violence and conflict. Violence upsets the peace of a community, which may seek to temporarily resolve that violence through “scapegoating”. That is, they redirect their collective anger towards one person (or group) – the war of all against all becomes the war of all against one. Violence against the one, perversely, brings the community together and pacifies the violent antagonism that might otherwise tear the community apart completely. The blame which they might otherwise have put on the competitor group is transferred to the relatively weak and defenseless scapegoat. Girard does not defend this process as right or good, but he explains it as being deeply ingrained in history and in mythology. Girard’s account of scapegoating and violence provides a very good explanation for why persecution against minorities takes place. Problems and tensions which exist among different groups lead to scapegoating, not because the group scapegoated is in any way responsible, but because the collective violence of scapegoating reduces division among the different violent groups. This scapegoating mechanism can only function when and to the extent that those involved genuinely believe that the individual or group being punished is guilty in some way. Some old myths, like the Greek story of Oedipus Rex, involve a scapegoat who is justly expelled for some real misdeed. Judaism and Christianity, though, challenged and transformed that story. Joseph, for example, was expelled by his brothers as a scapegoat, even though he was innocent. Unlikely many myths from other traditions, the story is told from Joseph’s perspective as an innocent victim, and he is eventually used by God to save the family and community. Jesus, the completely sinless victim, was unjustly scapegoated and yet redeemed humanity through his suffering. So perhaps, following Girard, our response to the persecution of minorities should be to try to challenge the scapegoating mechanism through new ideas and stories which show the victim’s perspective and the victim’s innocence. It is good to elucidate doctrines of human rights, but those doctrines only mean something if they are rooted in a deeper challenge to the validity of scapegoating.